What's the Point of Marriage?

The younger generations are rejecting it, but at the cost of their long-term happiness

June 2023

IT’S EASY TO be discouraged about marriage. Society no longer insists upon it as a path to respectability or even parenthood. Sex can be had readily and heedlessly outside of it. Despite decades of feminist counter-messaging, men still hold the keys to deciding if and when a couple will marry — and most men seem content to hang onto those keys longer and longer.

According to the latest data from the Pew Research Center, the majority of millennials are simply deciding not to tie the knot — a whopping 56 percent. It doesn’t look more hopeful for the depressed and isolated Gen Z generation. They are reluctant even to have sex with each other: Those who are 18-25 are less sexually active than adults in their 30s and 40s. One in four 18-24-year-olds has never had sex.

And why shouldn’t these generations be discouraged? As I wrote in the last newsletter about parenthood, from the outside looking in, marriage today doesn’t seem like a great idea. Younger people have observed the high divorce rates of their Boomer parents, job instability, the high costs of forming a household and family, etc. They seem gripped by a general aversion to commitment. “There’s a lot of fear around marriage and getting trapped into something that may not be good,” a millennial named Carol Polus observed here, apparently speaking for many. “A lot of people are just wanting to go on a journey with someone before they commit to something that big.”

And let’s admit: Those of us lucky enough to have sustained reasonably happy and long marriages have not been great spokesmodels for our brand. The actress Emma Thompson has defied Hollywood divorce odds by remaining contentedly married to her husband of 20 years, Greg Wise. But as Thompson recently told the Radio Times,

“It's philosophically helpful and uplifting to remember that romantic love is a myth and quite dangerous. We really do have to take it with a massive pinch of salt. To think sensibly about love and the way it can grow is essential…. Long-term relationships are hugely difficult and complicated. If anyone thinks that happy ever after has a place in our lives, forget it.”

This is a woman who met her future husband on the set of a dramatization of the very romantic Sense & Sensibility by Jane Austen. So … Thompson should know?!

Alongside the trashing of the “myth of romance,” the young hear much repetition of the warning about marriage being “a lot of hard work.” A 2019 article in Martha Stewart’s Weddings sounded the alarm bells to a future bride and groom:

Whether you've been married for just a few months or are inching towards a full decade as Mr. and Mrs., you've probably come to the realization that a marriage-like any other relationship-is hard work.… “Our culture, especially in the media, promotes the idea that the best part of a relationship is at the beginning, when people feel a tremendous sense of connection. However, this is unsustainable, and over time differences begin to come to the surface," explains Stephanie Buehler, MPW, PsyD, licensed psychologist, and AASECT-Certified Sex Therapist at Hoag for Her Center for Wellness. "For committed couples, it requires work to understand and navigate those differences, and the 'work' is communication between partners that is respectful and attuned to emotions as well as ideas."

When put this way — by a licensed psychologist and certified sex therapist no less! — a newly infatuated couple might worry that they may be unqualified for a future as husband-and-wife. Perhaps they should take a course in marital communications, or go for the masters degree in “Why Does He Always Want Sex When I’m Tired/Why Is She Being So Passive Aggressive But Saying Everything Is Fine” school of Marriage Management.

I’m not trying to make light of the very real challenges of sustaining a committed relationship over time. But as I approach my own 35th wedding anniversary at the end of this month, I worry that those considering an engagement — or simply contemplating it as a future state — are bombarded with cautions and warnings to the point of deterrence.

I’ve learned to be wary of converting my own experiences into advice for others. I haven’t always felt this way. If I’d sat down to write this essay after my first decade of marriage, I’m sure I would have been loaded to bear with helpful suggestions. (In fact, I probably did write such an essay.) But the longer I remain married, the less I have to say about it. Contra Tolstoy, all families are not happy in the same way. As I’ve grown older, I’ve grown — if not wiser — more uncertain about how things truly work (maybe that is wiser). Pure, dumb luck probably has more to do with hitting the happiness jackpot than anything else. (My husband David, more pessimistic by nature, points out that one key to a lengthy relationship is not dying in the middle of it.)

Most of the advice I’ve received - even most of the good advice - I have repeatedly disregarded. I must have heard a thousand times: “Never go to bed angry.” (Yeah, right. I’ve gone to bed furious more times than I can count.) “Make sure you take time for yourself.” (Nice thought when a spouse is away and two children under five are clamoring for your attention.)

But one thing I can say: the most common piece of advice that sounds the most wise is also perhaps the most unhelpful. This advice teaches people, and especially women: Above all else, it’s important to retain your identity and independence in any long-term relationship. In fact, you should not think of committing yourself to another person until you have a solid understanding of “who you are.”

Why is that the worst?

On its face it seems sensible enough. You never want to lose sight of your unique strengths, ambitions, or interests. Women do need to guard against our sex’s tendency to surrender entirely to others’ needs, denying and obliterating ourselves in the process (feminist Gloria Steinem once dubbed this tendency “compassion disease”).

Yeah, so don’t do that. But also don’t believe that your “true self” — once discovered and established — is something that can be separated and protected in its own padded box. Any two people approaching a relationship determined to hang on to their independence, their “separate selves,” are taking steps on a path that will likely lead to separation altogether.

My late father-in-law, Murray Frum, once helpfully put it this way. Murray said (I paraphrase): There is you. There is your spouse. Eventually there may be children. And then there is the marriage. At any given moment, each one of the individual elements will have needs. Sometimes those needs must be given immediate attention. But the most important element, always, is the marriage — because if it is not treated as the priority, all the other elements within it will suffer. Murray and my late mother-in-law Barbara were both very strong personalities, very different from each other. Yet they enjoyed more than three decades of an enviably happy marriage until Barbara died tragically early at the age of 54. Together, they exuded the contentment and compatibility that a passerby would detect in a glance.

So there will be times when you feel unhappy, or neglected, or frustrated, or whatever. One of your children might be going through a difficult phase. Your spouse might be facing issues at work. There could be financial troubles or a sudden, serious illness. These situations will demand immediate attention, often at the expense of others. Like white cells racing to fight an infection, the family unit will need to rally all its emotional and supportive resources to address the problem and remain healthy.

Yet through it all, the marriage must be kept in mind as its own separate being that, if neglected, will doom all the other beings that depend upon it.

This commitment becomes especially indispensable when the challenge the couple confronts is not an emergency, but the familiar and predictable human condition of parenthood. If there is such a thing as the fog of war, there is definitely a fog of new parenthood. Sleeplessness, exhaustion, raging hormones, and the newness of the situation can lead to fights or an inability to cope with anyone’s needs but the child’s. But even during this fog, while all white cells gather around the bassinet, the marriage must be kept in mind; if neglected, it will begin squalling loudly as well.

ONE OF THE kindest, most thoughtful acts my husband David did for me as a new mother was to recognize the importance of getting me out of the house, away from the baby. We lived then in Manhattan, and he was working full-time in an office downtown. Money was tight and the financial contributions I made as a journalist before giving birth weren’t going to resume any time soon.

Still, David saw that for my sake — and our sake — I needed to see myself as something other than a zombified, baby-feeding machine. He knew I fretted about whether I would ever be able to write anything again other than a shopping list. So he carved out enough money from our budget to allow for some weekly part-time help. He never told me what sacrifices he made to do it. He just impressed upon me its necessity.

I protested that, even with part-time help, I was in no condition to resume writing, physically or mentally. I’d just end up feeling guilty about the expense.

He said: “Danielle, if this simply allows you to go get a coffee and read the news undisturbed for an hour, it will be worth it.”

David was right. As any new mother will appreciate, the opportunity to shower, to dress in something other than pajamas or sweats, to leave the house unencumbered just to walk in a park or sit at a café, is critical to one’s mental health. Eventually I would use those hours to start writing again. In the short term, they restored my sense of self.

Indeed, throughout those early years, while I was the primary caregiver to our young babies, David continued to be the primary caregiver to our marriage. He saw my tendency to capitulate to our children’s needs, to forget about my own — and in doing so, our romantic union risked devolving into a tired, sexless arrangement between two co-workers.

I remember when our first child, Miranda, was maybe six weeks old. She’d begun reliably sleeping between 6 and 10 p.m. We lived then in a third-floor walk up at the northern extremity of the Upper East Side. Directly across the street was an Italian restaurant we liked. One warm summer evening, David urged an experiment: Would our baby monitor’s signal extend to one of the sidewalk tables? He carried the little walkie-talkie over to the restaurant while I stayed in Miranda’s room to conduct a voice test (camera monitors didn’t exist then). It worked! He heard everything clearly. I left the apartment and joined him for dinner.

Of course this would get us hauled up before child protective services today (and maybe it would have done so then, had we been discovered). But from our outdoor table we had a clear view of our apartment, including the window of Miranda’s room. If a fire alarm went off, or she so much as peeped, we could be back upstairs in under a minute. I still remember the thrill of that first “adult meal.” As the lights on the walkie-talkie captured the occasional gentle snore, David and I were together as before: drinking wine, holding hands, discussing the topics of the day on a beautiful New York night. Score one for the marriage.

In the coming years, I’d bear my fair share of marriage tending. Like any long-standing couple, we’ve faced challenges — illnesses, deaths, financial stress, all kinds of life stuff. We’ve had big arguments and petty ones. My anger is explosive; David’s is slow and simmering. Over time we’ve had to work out our own terms of engagement: I’m not allowed to huff out of a room; he has to speak up rather than seethe. Domestic tasks have shaken out pretty much to sexist stereotypes, not least because they align with our genuine strengths and interests. I love cooking. He likes cleaning up while listening to an audio book. I accept that he will never rinse the sink or wipe a counter (I can’t explain why — it’s like he’s coded not to do so). He accepts I’m pretty much hopeless at dealing with tech problems (my own coding issues). And so it has gone for more than three decades.

But would I describe our marriage as “hard work”? Maybe — if I’d never been exposed to the concept of marriage that David learned from his own parents, as articulated by Murray. It’s so easy to be swept up by the immediate. It’s natural to fear succumbing to another’s needs, or to grow resentful of others’ demands. It’s human nature to let things slide rather than confront them head on. God help those who find themselves in abusive relationships (#TinaTurnerRIP) or discover belatedly they’re attached to the wrong person. My own parents divorced when I was five. I’m grateful to have grown up with the example of my mother’s very happy second marriage to my beloved step-father. If you’ve never experienced a “good marriage” first hand, it’s understandably difficult to imagine what it would look like or how you might achieve it for yourself.

Approaching the idea of marriage as its own separate entity , however, helps to navigate a relationship through the familiar ups and downs. It promotes respect for each other’s needs and desires in the context of other competitive demands. Rather than snuff the individual self, it recognizes that self — and recognizes, too, that individual selves can change, adapt, and thrive in union. We’re not statues that merely weather over time. I sometimes think a successful marriage resembles two intertwined vines that, if tended well, will grow tall and sturdy over the seasons. Try to pull them apart, you will damage or even kill one or the other, or both. Together, they become strong as a tree trunk.

Those of us in enduring relationships need to do a better job telling younger generations about marriage’s positives. Familiarity doesn’t have to breed boredom. Romance doesn’t have to die. The first rushes of passion are like the fiery launch of a NASA rocket. Love is the fuel that sustains the long journey ahead. The fuel must be monitored, so it can be topped up as needed. The payoff is a life spent with a companion who knows you and understands you like no other; with whom intimacy is enhanced because of its very familiarity.

I remember the sadness of a young couple who broke up after a couple of years of living together. The young woman said about her now-ex partner, “I know he prefers The Borrowers to Stuart Little. What am I supposed to do with that information?”

I totally understood. I like that David and I can guess what the other will order from a menu. That he remembers details from my childhood I’ve forgotten. That we sometimes refer to oft-told jokes as “Joke No. 87.” But mostly I like that we share a lifetime of experiences and friendships together, with the bonding glue of having raised a family.

In the end, it’s this central relationship that will determine whether we have lived a happy and fulfilling life. Or not.

So, to those of you fearful of dipping your toe in commitment: Don’t be scared. Marriage is like any other adventure. Sure, there’s work. But remember that it’s work always in service of joy, fun, companionship, life fulfillment — and the greatest love there is, or ever will be.

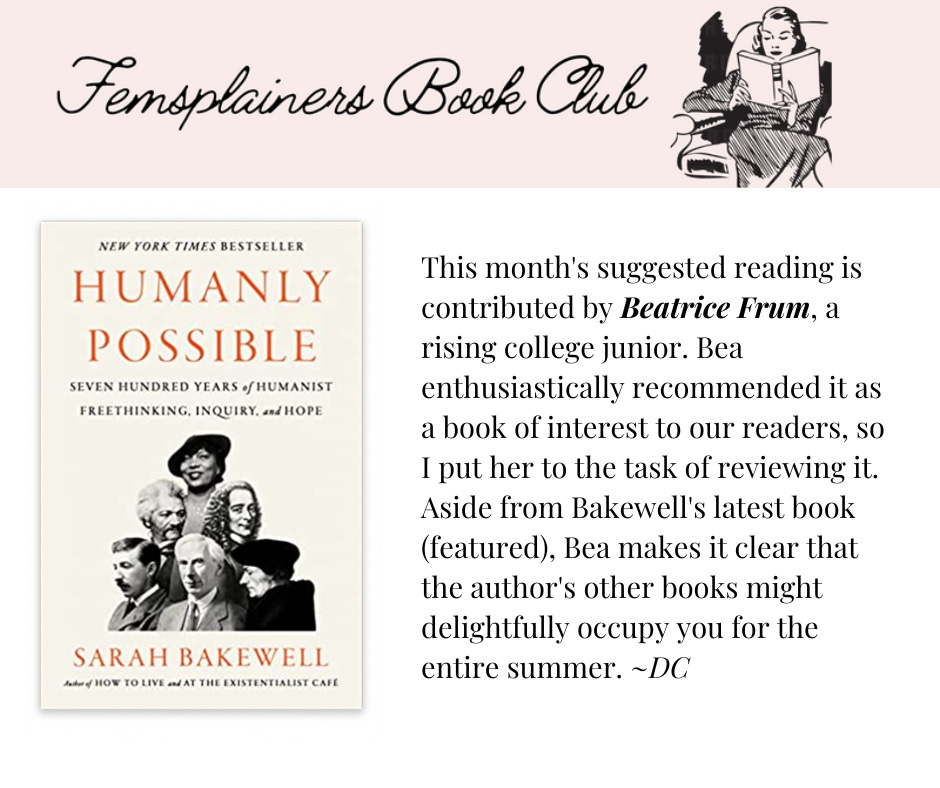

SARAH BAKEWELL KNOWS how to write intellectual histories. Author of At the Existentialist Café: Freedom, Being, and Apricot Cocktails and How to Live: Or a Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer, the distinguished historian offers informative and witty portraits of the thinkers who have shaped modern life. Bakewell’s most recent book, Humanly Possible: Seven Hundred Years of Humanist Freethinking, Inquiry, and Hope, is no exception. Bakewell discusses the intellects throughout history who have sought to cultivate a philosophy that places our relations with others at the center of our understanding of the world. She writes of those who dedicated their lives to the pursuit of knowledge, often putting themselves at odds with religious structures or authoritarian governments, all to prove that we must value those around us, and the capacity humans have for peace and progress. What makes this book especially wonderful is not just Bakewell’s encyclopedic knowledge, but how she makes each thinker come alive to her readers, making us feel that we just met them at a dinner party. We learn of Petrarch’s obsessive approach to acquiring books, John Stuart Mill’s epic love story with his wife, Harriet Taylor, and Robert Ingersoll’s favorite pleasures (good soup). But besides that, Bakewell shows why Humanist thinking has both historic and modern importance: It’s a philosophy that promotes thinking, empathy, and hope. A quote from George W. Norris, that Bakewell cites, articulates her overall message: “Training in the art of thinking has equipped me to see through the shams and humbug that lurk behind the sensational headlines of the modern newspapers, the oratorical outpourings of insincere party politicians and dictators, and the doctrinaire ideologies that stalk the world sowing hatred.” ~Beatrice Frum

WANT TO CONTRIBUTE a suggestion to our book club? For our summer issue, we’ll share a selection of reader choices. Forward us the book title, and a few sentences on why you recommend it, to contact@femsplainer.com. Deadline for entries is June 15.

MY MAY NEWSLETTER, which worried about Millennial and GenZ generations’ decline in motherhood, set off a Patriot missile amongst the pigeons. Clearly I’m not the only one of my generation to fret over it — and many of you appreciated my view that too often the negative side of parenting is exposed while the profound and massively outweighing benefits go unremarked upon. But maybe most heartfelt reply came from Ryanne, a GenZer herself, who made a strong and insightful case about what was going on amongst her peers. I reproduce it fully (with light edits) below, followed by some other reader comments. Thank you everyone for taking the time to share your thoughts. We love hearing from you. ~DC

Ryanne, via email:

I CAME OF age listening to and reading your content, and appreciate your work immensely. I have a few thoughts to add in regards to this article.

While you touched on some very real reasons that Gen Z/young women (I am 21 for reference) are not having babies, I feel that you have barely scratched the surface. I feel very passionately about this subject and want to bring some aspects of it to light that you may not have considered. I’ve had a few similar conversations with my Gen X mother, but I’m realizing that even Millennials don’t understand the plight of Gen Z.

The root cause I think is this: Never has any other generation of women been so removed from the dignity, splendor, and joy of their femininity. The world is not only externally effed-up, but far more internally/philosophically/socially effed-up than it was in for previous generations that dealt with famine, war, external hardships, etc. They had at least knew that motherhood ought to be noble, even if they didn’t really feel that way in the moment about it.

I think that relativism and despair are the biggest reasons for the lack of babies. And not despair in the Gen X and older sense, when something externally isn’t going your way, but a much deeper despair and exhaustion. I have often felt that my generation is in the last scene of the “Neverending Story,” floating through the Nothing, trying to hold onto the last pieces of rock from Fantasia.

Gen Z does not know what reality is. Gen Z does not believe in natures, or anything for that matter. The highest possible good is “whatever works for you”. Gen Z has almost no purely external/material/physical reference points that aren’t filtered through a screen. And Gen Z feels incredibly resentful of older generations for having taken away any and all structure that would orient us in the right direction so that you could placate your consciences and do whatever the hell “made you happy”. Structure that we should have been raised with was taken away in favor of moral relativism and hedonism because older adults became lazy and complacent, and refused the call to be virtuous. A friend of mine likened the Boomers to Kronos. I agree with him. Gen X at least got some of the structure that the Boomers grew up with.

When you mention that we are in the most materially prosperous world now, so why shouldn’t my generation of women be glad to be having babies, the answer is: Our youth has been stolen from us. The things that used to make being young a joy are now in constant question. My generation of women is fighting to figure out basic truths that Boomers and Gen X women never had to give a thought to; so it doesn’t surprise me that we wouldn’t want to devote ourselves to a child when we have been constantly fighting our whole life to just orient ourselves in a world where down is up and up is down so that the Boomers can have free love and Gen X can say “whatever works for you.”

Even in all that I have typed here, I have barely been able to go into why young women are terrified of our fertility. We are exhausted, hurt, and tired. We feel lied to by generations that we know aren’t trying to lie to us, but simply don’t understand the internal anguish that we deal with daily that they never had to go through.

Ryanne, you make many powerful points here. I won’t reply to them individually, but am deeply impressed by your description of the overall “relativism and despair” of Gen Z. No doubt some of that arises from the current wisdom that posits sexual identity is unrelated to biology, a topic I wrote about here, “When the Sexes Blur, There’s No Sex.” I would very much like to devote a newsletter to perspectives from your generation. Readers, do you have thoughts on this topic to share? ~DC

Meanwhile Lonna, via email, took a more pessimistic, if eloquent, view of motherhood:

IT’S AMAZING TO me that while psychology consistently shows that too much choice makes people unhappy, we as a society insist that everyone must have as much choice as possible. Thus, we have Millennials struggling with the choice to have children, and Gen Z struggling with whether to be a woman at all! And happiness continue to plunge.

Anyway, as a Millennial I have some issues with your cheery attitude toward childrearing. But when I think about it deeply, I guess I would have to blame feminism. (Yes, my old fashioned conservative dad is probably right: Feminism is the root of all evil. Okay, not all. And not actually evil. But certainly some unhappiness.)

We told women to stop thinking about themselves as baby machines. We told them to develop hobbies and careers. We encouraged them to create identities that don’t include children, or families, or even spouses in many cases. Then, we give them the choice: Give up this identity and everything that’s given them joy until now, in exchange for a baby… or don’t. Why are we shocked by the results?

And yes, children are sweet and fun and hilarious, but it’s hard to appreciate that if you’re resentful and mourning the lifestyle you gave up. My oldest is six and I’ve really just gotten to the point of acceptance. You probably think I’m being dramatic. But here’s a list of things I enjoyed before babies:

- Gym

- Jujitsu

- Mud runs

- Weeklong backpacking trips through national parks

- Whitewater kayaking

Some of those things became impossible due to long-term effects of pregnancy on my body (this is a problem for more women than is obvious). Some I just don’t have time or energy for, between the extra labor and reduced sleep. And some, the kids actively ruin.

For example, since the kids don’t have the stamina for backpacking, we tried doing overnight canoe trips. But then my oldest decided he was absolutely unwilling to go through any rapids, no matter how tame. My middle kid pukes in the car, limiting how far we can drive. And the baby is a carseat screamer. It feels like every attempt to claw something back for myself gets wrecked.

At this point, my sole hobby is gardening. And my primary gardening pest is the Helpful Toddler, endemic to just my garden. (Close behind is the Ambitious Child, who only wants to grow impossibly large squash in our tiny garden.) The lack of personal space in my life feels suffocating.

And let’s not get started on the career derailment. When I was an entry-level and realized I needed to learn AutoCAD, I bought an 800-page book and plowed through it every night until I was proficient. Now I can barely sit at my desk at work without getting distracted by childcare-related worries. This is not a good thing.

Do the adorable bon mots and snuggles make up for the losses? I’m trying to stop asking this question, because it’s moot, in any case. I have what I have, and I need to accept that. But I don’t think the choice is as simple as you make it out to be.

That said, I do notice a certain class of childfree older women who love getting down on the floor with my kids, while swearing they have no maternal interests. And then I'm quietly grateful that, whatever regrets I have related to children, it won't be my biology doing the regretting.

Last, we received this email, from Tom in Ottawa. He was commenting on our April newsletter, in which Danielle wrote about turning 60: The Secret to Staying Young:

I ENJOY YOUR articles, and as I’ve reached the ripe old age of 63 this one was particularly pertinent, although I’m male.

I’m really sorry, but not surprised, that women who reach your age feel that they are becoming invisible. I think it’s a sad comment on men, and perhaps on women as well. I feel that in my 60s I have a great deal to contribute, and so far I find that I’m being treated with commensurate respect and attentiveness. You’re clearly a very capable person, and deserve the same.

I think you’re bang-on with the rest of your article, and that’s the course I’m trying to follow in my “autumn” years. In terms of not being respected “just” because you’re no longer gorgeous, I’m afraid that I don’t know what to suggest. I thought that the great feminist fight of the 70s and 80s had made it clear that this is unacceptable behavior, but clearly I have overestimated people’s thoughtfulness.

The one thing I CAN suggest is, don’t let it get you down. For every man out there who’s a jerk towards older women, there’s someone like me who feels that their life experience makes them well worth engaging, and to hell with the 20-somethings. Fortunately, in the little that you and David have discussed your relationship, I get the feeling he’s another one.

THAT’S ALL FOLKS! Stay tuned for our summer edition, after which we’ll take a break until September. (Well not really — I’m going to work very hard to finish my novel. More on that anon!)

When I first started reading the article I initially got angry at your statement ‘men still hold the keys to deciding if and when a couple will marry’. Seemed like the usual - it’s all men’s fault. I realize that may not have been your intent. It must be discouraging for young men to be constantly demeaned or blamed by society today. I think men are worried about marriage because family court is usually very biased against them. Particularly if theirs a false accusation of abuse. They often come out on the losing end with custody & finance.

On a positive note: I was married to a wonderful women for a very long time. Sadly, she died, but we were blessed with a lovely life, children & grandchildren. I applaud your beautiful & realistic description of marriage and your sage advice. It’s spot on!

My parents told me that it’s not about giving 50/50, but about each giving 100%. I think it’s also very important to respect each other. When I was growing up, dads were celebrated for their masculinity & moms for their femininity. Within a very broad range. As you so eloquently expressed, there will be difficult times. However, most things that bring us true, lasting joy are difficult. My advice to young people is to be cautious, wise & thoughtful, but don’t let fear rule your life. Marriage can be one of life’s greatest experiences.

Great article! I agree with pretty much everything, but one detail has caused me a lot of heartache. Marriage is "till death do us part", which is a LONG time! I'm delighted that you and David are doing so well, but my story didn't have the happy ending. After 40 years of marriage, I decided to end mine, for reasons that I consider valid. Note that my ex is a very good, very nice person, but over the years things between us had changed. She was very upset, and one of the things that she quite rightly threw in my face was that I had committed to her for the rest of my life. In this era of 90 year lifespans, that's not realistic. In my opinion commitment is still important, and we need a mechanism for it, but it can't be forever. I will never marry again, and I will recommend against it to people for exactly that reason.