March Madness: Men Are Not (Always) to Blame

For Women's History month, David Frum argues there may be other causes for women's thwarted ambitions besides sexism

March 2023

YOU MAY WONDER why a man is contributing our Women’s History month essay. Fair point, but sometimes we femsplainers must allow mansplainers their voice. Especially when they volunteer to write for free. Actually, as Atlantic contributor and full-time husband David Frum diplomatically notes below, his contribution to this newsletter was not entirely voluntary — but neither will it go uncompensated. While I don’t like bean-counting in a relationship (“It’s your turn to unload the dishwasher”), David may find himself pleasantly relieved of some domestic chores in coming days. There might even be a Steak Diane in his future. The reader may be assured we do not exploit our writers.

Also in the Women’s History Department: Our “Femsplainer of the Month” feature for March honors female pioneers in space. I’ve been marveling at the extraordinary images of galaxies far, far away being beamed back to earth by the James Webb Telescope. Then I marvel at how … ho-hum? … the public reaction to these images has been (myself included). Billowing networks of gas and dust, cosmic spirals… Cool! Scroll down. Billions of blinding stars, ghostly “fingers” resembling the hand of God … Amazing! Swipe left.

Perhaps because the photos are being delivered via telescope, they lack the human interest we feel when we shoot people into space to take them in person. Maybe they’d get a bigger reception if Ryan Seacrest were hosting them. But I’m old enough to remember when the first grainy images of earth fluttered across our television screens — and the mass excitement watching Neil Armstrong take his first steps on the moon (July 20, 1969). Fourteen years later, the aptly named Sally Ride became the first American woman to venture space. There was some anti-feminist snarking when the grinning, perm-headed astronaut joined her four male colleagues aboard the space shuttle, on June 18, 1983. But Ride, a scientist, went on to have a consequential career at NASA. She developed and was the first astronaut to operate the robotic Canadarm; she led NASA’s long-term strategic planning as Director of the Office of Exploration; and she served on the presidential commission that investigated the tragic explosion of the the Challenger in 1986, alongside Armstrong and Chuck Yeager. Thanks to Ride, more women would prove they had the right stuff, too.

As always, thank you to those who subscribe to The Femsplainers. We welcome your comments and questions (you can leave them at the bottom of this newsletter or send to contact@femsplainers.com). And if you enjoy the newsletter, we’d be very grateful of you please click on the pink button below. Everything is more fun with friends! ~Danielle Crittenden

MARCH IS WOMEN’S history month. To mark the occasion, a man has stepped forward to grasp the microphone from the editor of this newsletter. Could there be a more apt commemoration?

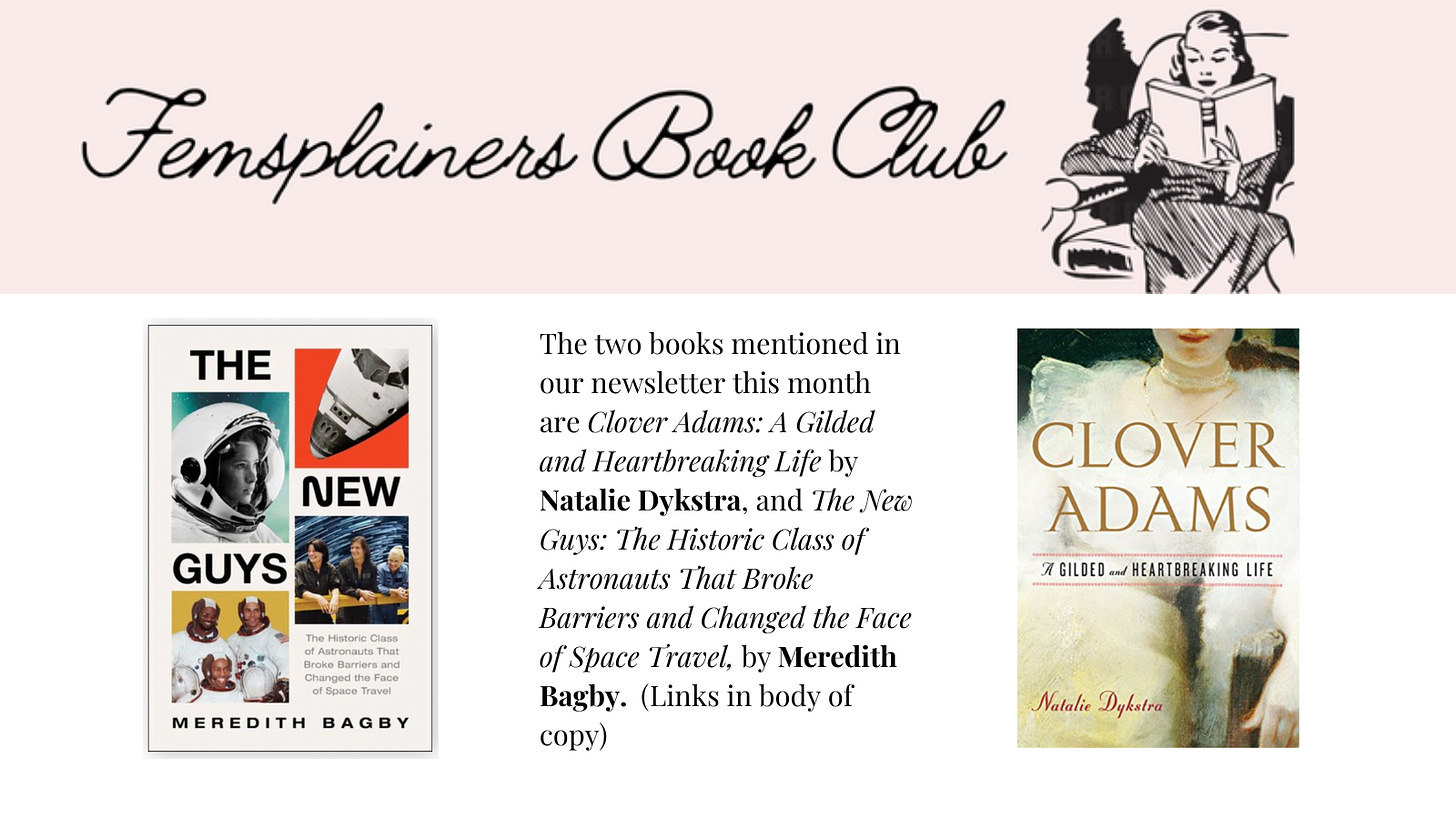

The microphone-transfer began over breakfast coffee a few days ago. “If you’re going to keep talking about that Clover Adams biography, at least make yourself useful about it.” Danielle was referring to a book that occupied me in mid-February, Clover Adams: A Gilded and Heartbreaking Life, by Natalie Dykstra, published in 2012.

Clover Adams is perhaps best remembered today for inspiring an astonishing work of art: a bronze memorial statue by Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The statue marks the burial place in northeast Washington, D.C. that Clover shares with her husband, the historian Henry Adams.

Clover died by suicide. She had discovered a midlife enthusiasm for photography. In those days, the development of negatives into finished pictures involved dangerous chemicals. Clover drank some in early December 1885. She was 42 years old. When Henry Adams died of a stroke in 1918, Dykstra writes, a niece discovered in his desk drawer “a half-empty vial of potassium cyanide in the top drawer of his writing desk - Henry had always kept nearby the means of Clover’s death.”

In the first flush of feminist history-writing in the 1970s, however, it was Henry Adams himself who was often suspected of being a more indirect means of Clover’s suicide. Those were the days of the accusatory counter-biography: the big studies of literary women deprived of their due by the devouring ego of husbands and lovers -- or even driven to madness and suicide. The tragic roll mustered names like Jane Carlyle, Zelda Fitzgerald, Sylvia Plath, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, Virginia Woolf.

Clover Adams always figured awkwardly in that list. For starters, she and Henry enjoyed unusually secure positions in American life. Henry was of course the great-grandson of President John Adams; the grandson of President John Quincy Adams; the son of Charles Francis Adams, ambassador to Great Britain during the Civil War. Henry himself served as the principal secretary in that important embassy. After the war, Henry was hired by Harvard University where he pioneered modern historical scholarship in the United States. Henry and Clover both inherited substantial affluence — nothing like the colossal wealth of the great industrialists of their day, but enough to support city and country houses, cooks and maids, and well-informed art collecting.

They shared intellectual interests and trans-Atlantic friendships with writers and artists. Clover read French and German, and it was the witty Clover rather than the pricklier Henry who seemed the main attraction at their impressive salons first in Boston, then in Washington, and on extended visits to Britain and Europe. They never had children. Their marriage was more companionable than passionate or romantic — but still, if you had to live in an age before central heating and modern dentistry, their lives were about as enviable as it got.

For sure, a biographer can bring a feminist bill of complaint against Henry. Dykstra complains that Adams both idealized women and also condescended to them. She quotes from one of Henry Adams’s letters: “The woman’s difficulty is that she is fooled by her instincts and sentiments, which are at the same time her only advantage over the man.” Dykstra tells in some detail a story about a prestigious magazine requesting the right to publish one of Clover’s photographs — an invitation that Henry vetoed (on the maybe not unreasonable grounds that the photograph would illustrate an article that he did not want to write). In the absence of children, the rhythms of the Adams household were organized around Henry’s work and Henry’s wishes.

In his mid-40s, Henry became fascinated by an unhappily married woman 20 years his junior. The young woman appreciated the flattering attention of the great writer. There’s no evidence the relationship was sexually consummated — or that either Henry or the young woman ever intended that it might or should be. Clover’s and Adams’s friend Henry James put on the record his disbelief that it ever was.

The friendship or affair or whatever it was coincided with another traumatic event in Clover’s life, the death of her beloved father. Clover had suffered mental health crises before. In the second half of 1885, she plunged into a profound depression. Henry struggled to find treatments, including a six-week, train-and-horseback tour through the Virginia countryside. Nothing availed.

After Clover’s death, Henry destroyed all her letters to him. He made no mention of her in his famous Autobiography. Her name is not inscribed on the Saint-Gaudens monument. A few weeks after her death, Henry moved out of the rented house he had shared with Clover into the handsome new home that he and Clover had designed together, but where she never lived. (The new house was located at H and 16th Streets, on the site of what is now the Hay-Adams hotel.)

The record of Henry’s grief survives, however, in anguished letters he wrote to friends and relatives. “The world may come and the world may go; but no power on earth can annihilate the happiness that is past.”

When Henry Adams informed his parents of his engagement to Clover, his outspoken mother protested: “Heavens! — no! — they’re all as crazy as coots.” The “they” here were Clover’s family. Clover’s grandmother had collapsed into depression after the death of a son and isolated herself from her other children for the rest of her life. One of Clover’s aunts committed suicide. In 1901, Clover’s brother jumped out of a third story window. He died a few weeks later.

Adams’ mother expressed the rough folk wisdom of the 19th century: madness runs in families. The dominant psychological theories of the early 20th century rejected claims of heredity. The human being was born blank. The human psyche was formed by its reaction to childhood events. The Freudian school explained depression as a reaction to early trauma. A child was rejected or harmed by a parent. The child felt anger - then guilt for its anger. If the anger and guilt went unresolved, depression followed.

Freud’s theories had room for blaming either parent for the child’s later-life unhappiness. In practice, however, Freudianism often ended up pointing the finger at the mother. In understandable reaction, post-Freudian feminists redirected the blame for mental illness from family to society. People weren’t depressed because their parents had somehow failed them. People — and especially women — were depressed because of the objective realities of their lives in an unjust or uncaring society. In 1972, the feminist psychotherapist Phyllis Chesler published a hugely influential book, Women and Madness. Women needed to be told, she wrote, that “it’s normal to feel sad or angry about being overworked, underpaid, underloved; it’s healthy to harbor fantasies of running away when the needs of others (aging parents, needy husbands, demanding children) threaten to overwhelm her.”

Then we come to Clover Adams: not overworked, not underpaid, not overwhelmed, and not even exactly underloved — and we realize, we may need a new theory of the causes of despair and self-harm.

As the family theory of mental health yielded to the social, the social theory needs to yield to the biomedical: one that recognizes that the suicidal depression that killed Clover, her brother, and her aunt is almost as organic and hereditary as high blood pressure or cancer.

None of this is to say that the feminist critiques of society in general — or Henry Adams in particular — are necessarily wrong. Dykstra writes incisively: “Henry failed to recognize that a woman might want a share in what he himself needed — satisfying work to do, social esteem, and the possibility for self-reliance balanced with friendship and love.” That’s all true. Those are important things. But they are not remedies for suicidal depression — as attested by the many tragic cases of people who do have all those things, and cut short their lives anyway.

It would have been fun to know Clover Adams in her happier hours. Her insights could be fierce, but astute. Of her friend Henry James, she said: It’s not that "he bites off more than he can chaw, but he chaws more than he can bite off." Once you hear that assessment, you cannot unhear it. I’m not sure it would have been so much fun to know Henry Adams, even before he sank into the conspiratorial antisemitism of his later years. (He was certain that the French colonel Albert Dreyfus was guilty, solely on the grounds that betraying his country was a thing a Jew would do.) Fun or not, they were giant figures in American culture, history, and literature, and I am grateful to Natalia Dykstra for helping me know them better. But as to why certain figures in culture, history, and literature sink into madness and suicide, we need an account based on the science of the physical brain, not the critique of society — even the most justified critique.

The usual author of this newsletter declares it as her creed: “The personal is not political.” Nowhere is Danielle more correct than in the understanding of the deepest forms of grief and loss and sorrow.

Despite so many years in Washington, I’ve never visited Clover’s monument in person. When the weather warms, I’ll correct that omission. When there, I’ll try to communicate to her spirit that understanding is spreading, and cures are coming, for the disease that prematurely deprived the world of her — and her of a world in which her great gifts and great good fortune should have found greater joy.

The Sisterhood of Space

Front, from left to right: Sally Ride, first American woman in space; Dr. Anna Fisher, first mother in space; Kathy Sullivan, first American woman to perform a spacewalk. Back, left: Judy Resnick, who died in the Challenger explosion. Back, right: Shannon Lucid, the sixth American woman in space who, until 2007, held the record for most hours in orbit by any woman in the world.

These women were all members of NASA’s 1978 class of astronauts — a graduating class considered so groundbreaking they were nicknamed “The New Guys.” Not only did this class include women but also the first African American, Asian American, Jewish person, mother, LGBTQ person, and married couple to go into space. Their stories are now documented by author/filmmaker Meredith Bagby in her new book, THE NEW GUYS: The Historic Class of Astronauts That Broke Barriers and Changed the Face of Space Travel. Think of it as an update of Tom Wolfe’s classic The Right Stuff. A TV series based on the book is in the works with — natch! — Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks.

WE ARE STILL receiving comments about our January newsletter, Why Dating Apps Are Failing You. We are going to give the last word on this topic to “Sandra,” who wrote us this funny missive about why, as a single women, she has stopped using the apps. Spoiler alert: It does not lead to the romantic ending we would hope for. But perhaps Sandra will find love among our single male readers of this newsletter? Post a comment. Offer to buy her a drink! You never know.

First, I want to say I LOVE THIS! Oh how this is a breath of fresh air. Why? Because society has built a narrative about dating apps being the MUST DO if you want to meet someone. This coupled with the shame that often gets thrown around to single people who opt NOT to use the apps (maybe it’s because we have a brain and want to preserve our time, money, and well- being ) makes for an exhausting human experience.

I thank you for bringing this to the world’s attention. No one HAS to go on dating apps which by the way aren’t free — they cost money and a whole lot of time!

I have been on and off of that shit show for decades. Think Lava Life days. I hated it back then and I hate it now. The only difference is now I don’t bother with them. The tipping point for me was when I went back on to the app after having invested a shit ton of money and time on hiring someone to “perfect my profile.” I even got professional photographs. When all of that didn’t work out, I said, “Forget it! I’m not doing it anymore.” And you know what I started doing? I started actually LIVING.

I joined Jiu Jitsu and began lifting weights. I devoted myself to fitness and cooking because I loved it. I started hosting my friends and family over because I love them. I went for walks in nature. Basically, I got a life instead of wasting my time on coffee dates with people I had no interest in and who had no interest in me.

Now you’re probably thinking “Great end to the disaster dating app story right? Let me guess, she met them man of her dreams while back squatting 170 lbs…”

Nope! Getting off the apps and back into my life hasn’t “manifested” the love of my life. Unless you count the love of my life being “ME”.

I’m a lot happier. I like who I am and how I spend my time and money. I like not looking at guys and thinking, “You call that an athletic body?” before I swipe left and move onto the next guy to criticize underneath my breath. I like not feeling like a bitch and I like talking to guys as friends. I’d like to meet someone. I really would. And I hope it’s the way you described — with the real-life flirtations instead of texts, and the glances across the room instead of an emoji.

Thank you for contributing to the growing narrative that online dating is NOT a must do if you are single. Let’s reframe how we view dating.

Thank you. SANDRA

See y’all in April when, gasp, I turn 60. More on that later…

Feminism: A Jewish Psyop to Demonize White Women

MGTOW = Mostly Gay Transgendered Or Wimpy

http://www.renegadetribune.com/the-psychological-operation-to-blame-white-women/