Is That All There Is?

Half a Century of Sexual Liberation Has Brought Neither Sex Happiness

May 2022

IN MY FIRST BOOK, What Our Mothers Didn’t Tell Us: Why Happiness Eludes the Modern Woman (published in 1999), I made this opening observation about the effect of the sexual revolution upon my generation of women:

A huge social transformation had taken place between [Betty] Friedan’s day and mine. Had it made women any happier? … The answer was resoundingly no. My contemporaries [were] even more miserable and insecure, more thwarted and obsessed with men, than the most depressed, Valium-popping suburban [housewife] of the 1950s.

One of the chief reasons for this sad outcome, I’d write, was the failure of the Second Wave feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s to acknowledge biological differences between men and women, especially as it affected our aspirations and sexual desire. In the bedroom as in the board room, the hope was that by mimicking men we would achieve equal success. “The personal is political,” the thinking went, and the only thing that held women back from achieving their full potential was a patriarchy bent on suppressing women, much like the bourgeoisie oppressed the proletariat in the Marxist worldview.

So: out with the dishtowels, marriage, and motherhood; in with the power suits, sexual freedom, and unencumbered ambition.

This outlook backfired in many ways, as I detailed at length in the book. But with sex in particular, the personal turned out to be much more problematic than the political. As teenage girls, we were taught to go forth in the world like sexual imperialists, conquering and exploiting men with our erotic desires just as they had once conquered and exploited us. High school “health” classes provided the war plan: memorize these diagrams of female and male sexual organs; arm yourselves with these different types of contraception. The pre-internet, pre-MeToo world of television, movies, and women’s magazines took up the battle cry. “A pleasant-tasting lubricant such as Astroglide facilitates any hand action” and “Easy Orgasms — How to Make Them Mind-Blowing and a Lot Less Work” advised typical articles in 1997 editions of Mademoiselle and Cosmopolitan. Soon we would all be living in a world of unprecedented sexual harmony.

Or maybe not.

Carelessly, thoughtlessly, casually, sex — in the short space of a single generation — went from being the culminating act of committed love to being a pre-condition, a tryout, for future emotional involvement. If any.

And the lesson we took away?

Of all the promises made to us about our ability to achieve freedom and independence as women, the promise of sexual emancipation may have been the most illusory. These days, certainly, it is the one most brutally learned. All the sexual bravado a girl may possess evaporates the first time a boy she truly cares about makes it clear he has no further use for her after his own body has been satisfied. No amount of feminist posturing, no amount of reassurances that she doesn’t need a guy like that anyway, can protect her from the pain and humiliation of those awful moments after he’s gone, when she’s alone and feeling not sexually empowered but discarded. It doesn’t take most women long to figure out that sexual liberty is not the same thing as sexual equality.

Now let’s fast forward two decades — to today.

Thirtysomething Washington Post columnist Christine Emba recently went to take the sexual temperature of the Millennial and GenZ generations but was barely able to find a pulse. In her new book, Rethinking Sex: A Provocation, the outlook for women seems no less bleak than I found it in 1999. The “progress,” however, is that now men don’t seem to have it any better. Both sexes appear equally miserable.

Emba grew up in a Christian evangelical family and later converted to Catholicism in college. Unlike her peers, her religious beliefs protected her from having casual sex as a teenager, and she held on to her virginity into her twenties. But even while abstaining, she was made aware of the emotional carnage taking place amongst her friends, a carnage driven by their confusion over sexual equality.

What I heard again and again was contradiction: Having sex was a marker of adulthood and a way to define yourself — but also, the act itself didn’t really matter. Good sex was the consummate experience — but a relationship with your partner was not to be expected.

Emba eventually struggled with her faith, and with it, plunged into a sexual lifestyle similar to her straight peers. Her book is a treatise on sexual regret — a phenomenon she calls “heteropessimism”— and she is one of the few female authors who gives (some) validity to men’s disappointments and fears as well.

The woes of Emba’s generation and GenZ (also called iGen) are well known — and are particularly hard among the latter. Depression, anxiety, and suicide rates are soaring amongst them. As for sex? According to this important 2017 study:

Americans born in the 1980s and 1990s (commonly known as Millennials and iGen) were more likely to report having no sexual partners as adults compared to GenX’ers born in the 1960s and 1970s in the General Social Survey, a nationally representative sample of American adults (N = 26,707). Among those aged 20–24, more than twice as many Millennials born in the 1990s (15 %) had no sexual partners since age 18 compared to GenX’ers born in the 1960s (6 %).

The lack of sexual activity is particularly pronounced among young men who play a lot of video games (big surprise). Combine all this with the swipe left habits of online dating culture, and it’s not especially difficult to come up with reasons why a single woman or man would prefer no sex to bad sex with a stranger with whom they have nothing more in common than an algorithm.

As Emba notes, strategies to counter post-MeToo issues with sexual encounters don’t help with the root problems at play. Freshman seminars on “consent,” she writes, are “a case of providing a right answer to a wrong problem.

It’s not that students aren’t learning their lessons about consent …. The baseline norm is correct: Consent must be present in any sexual encounter; otherwise it is morally illegitimate. Having sex with someone who hasn’t agreed to have sex with you is unacceptable; criminal in fact.

But will more lectures on consent dissolve gender stereotypes, rebalance power differentials, explain intimacy, or teach us how to care? …[A]n overreliance on verbal consent might actually worsen this malaise: if you’re playing by the rules and everything is still awful, what are you supposed to conclude?

Emba quotes David, a 29-year-old software analyst, who compares making romantic overtures to “handing someone a loaded shot gun or something. I mean, most people will be fine with it, but …” Another man, a 35-year-old consultant in D.C., confesses that he would never flirt with or approach a woman in public, for example at a coffee shop. “I feel like that’s kind of an aggressive move in these current circumstances. I almost never see it. You stay in your lane.”

As the opportunities for meeting people IRL dwindle, dating apps have made the search for love more harrowing, not less. And it’s not just because they offer too many choices or reduce the act of seeking a life partner to shopping for a dress online. Emba makes the shrewd observation that — as with so much in the social media world — there is little personal accountability at stake and a lot of leeway for deception. If you meet someone at college, or through friends or community, there will be peers to answer to if you behave badly. “You can be rude, you can be crude, you can ghost, and no one in your circle of actual acquaintances will ever know unless you choose to tell them. No one can see your messages or your dick pics. No one will know what you get up to when (or if) you do meet up.”

SO WHAT TO DO? Emba doesn’t offer much of an answer, except for a vague and general call to action for singletons to rethink their attitudes towards sex and the way they behave (Ladies, you don’t have to have sex with someone you don’t like or barely know!). But there is no self-help, happy-ending aspect to this book: Emba herself does not seem to have gone off the grid and found the man of her dreams.

In part, that’s because Emba herself is still captive of the idea of an all-powerful patriarchy (even while giving air time to studies that show males faring no better than their female counterparts, and more often than not, faring worse in such things as mental health and education). But she does allow that there are biological differences between men and women. (It’s funny to type that as such an original and revolutionary thought, but these days it’s a strong stance to take for a progressive person, which Emba is). A woman still faces a biological clock; she likely does not see sex as a mere physical act or an end in itself; and unbridled sexual freedom has not brought us the happiness its early advocates hoped for. Everything depends upon how you manage that freedom.

But maybe Emba’s most valuable contribution to this ongoing discussion is her reminder to women that they have personal agency: Casual sex is not something “done to us” without our buy-in. We may not be able to change the attitudes of others, but we can change our own. We can examine what we really want and expect from a partner, and not pretend that depressing physical encounters are “empowering.”

My own addition would be to say that rather than regarding men as hostile forces, we need to bring them into the conversation, not just our beds. So long as we blame our situations on the all-purpose patriarchy, we will unfailingly, at some level, view ourselves as victims rather than protagonists in our own stories. Men are human too. We need them, and we need to understand love from their perspective as well as our own.

FOLLOWERS OF THE FEMSPLAINERS will know my obsession with all things royal. So I was literally counting the days for Tina Brown’s new book, The Palace Papers: Inside the House of Windsor — the Truth and the Turmoil, to arrive on our front door step. The minute it did I poured myself a glass of wine (hey, it was past noon) and cracked it open. It does not disappoint! Spending time with Tina is like having a modern day Samuel Johnson by your side, commenting on the passing circus. Brilliantly reported, her insights into the reality series version of The Crown are clever, hilarious, and often wicked. I’m currently in the midst of reading about Meghan Markle’s determined rise out of B-List (C-List?) stardom, which was full of ups and downs, and mostly downs. Tina writes unsparingly:

Meghan was always so close to fame, but never quite there: basic cable, not premium cable; inside the magazines but not on the cover. A UN advocate but not a UN ambassador, a local celebrity in Toronto but an unknown in New York. As she filmed the fifth and sixth seasons of Suits, she was well aware of the clock running down. She was about to turn thirty-five and still had not gotten the call from Anna Wintour to join the red carpet at the Met Gala.

Brown joined the Femsplainers podcast when her previous book was published, her equally gripping memoir of her days as editor of Vanity Fair, titled The Vanity Fair Diaries: Power, Wealth, Celebrity, and Dreams: My Years at the Magazine That Defined a Decade.

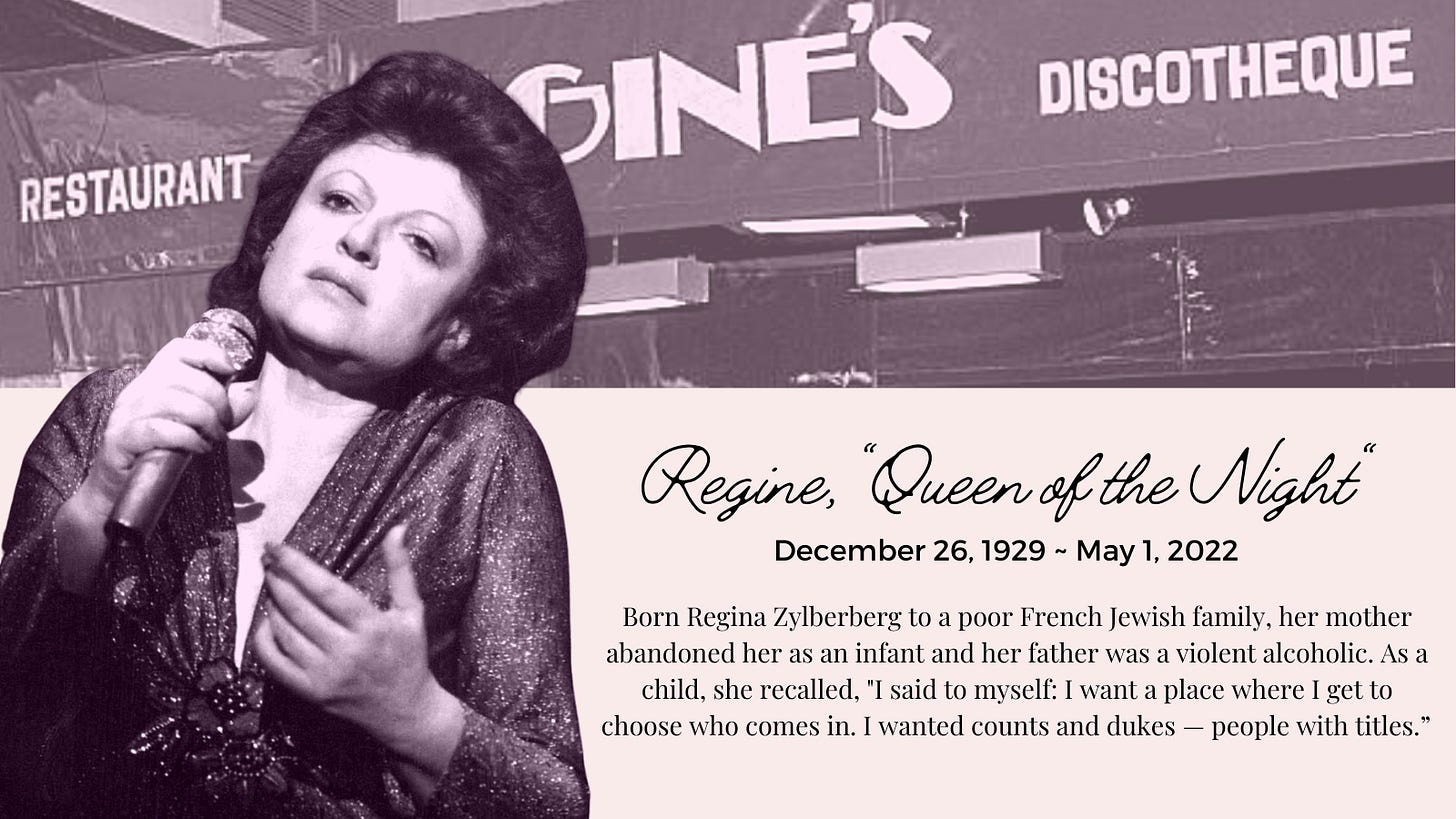

Regine would go on to found the first modern “discotheque” — in a small Paris nightclub in 1953. According to this wonderful obituary in the Washington Post,

The indomitable, crimson-haired woman known as Régine installed a linoleum dance floor and colored lights, standing on a chair and waving her hand at times to create a strobe-light effect for her clientele. To eliminate the awkward gap between songs — a silence that was filled by the sound of couples making out in the corner — she replaced the jukebox with two turntables and started spinning records herself.

“I was barmaid, doorman, bathroom attendant, hostess — and I also put on the records. It was the first ever discothèque,” she claimed decades later, “and I was the first ever club disc jockey.”

She’d realize her childhood wish. Le tout monde would soon flock to her later, eponymous, clubs — some two dozen around the world including a branch in New York City.

Our April issue, entitled “Can We Stop Negging Our Husbands?” received a lot of attention from the Monsieur Bovarys among our readers. The reflexive habit of women criticizing their partners in public — while posing as enlightened feminists just telling it like it is, or worse, positing it as “humor” — was epitomized in the recent book Foreverland: On the Divine Tedium of Marriage, by New York magazine advice columnist Heather Havrilesky. Among Heather’s choice terms of endearment for her spouse, Bill: “a heap of laundry, smelly, inert, useless, almost sentient but not quite” and “a snoring heap of meat.” Here are a selection of your comments:

From Bill:

I thought I’d back you up on the “don’t neg” thesis of your article—not on my (compromisingly husbandly) authority, but my mother’s. She, a very wise and often acerbic woman, used to condemn her friends’ unloading on their husbands, saying, “I don’t think they realize that, if their husband is so bad, for having married such an oaf, they look like an even bigger idiot.” She thought was an unworthy form of female bonding, and one likely to weaken marriages.

From Michael:

Why even publish this? She’s [Heather] clearly a miserable harpy; is there some market for miserable harpies everyone has been missing? I though supermarket romance novels had that market cornered. If I was her husband, the retort to this airing-out would simply be “oh yeah? Where are you gonna go?”

And from Cynthia:

With that much contempt, that marriage is doomed.

For the record, the author took us to task on Twitter. Havrilesky maintained that her book was more nuanced than the excerpts led one to believe and that her husband found it hilarious. If I were married to this person, I guess I would too. "Sure honey, it's VERY funny," she said, smiling and slowly backing out the room to Google "Food Taster for Hire."

Happy Mother’s Day to those celebrating! See you again in June.

Thank you, Danielle!!

Hope you paid Agnes and Charles for the use of their art. I can get you addresses if you do not know where to send the money.